Memes Mocking Their Patients

on Social Media?

Dr Kirsty Miller

(originally published 17 April 2024 in The Daily Sceptic)

Picture the scene: you have been struggling with your mental health. You eventually strike up the courage to talk to your GP, who refers you to a psychologist. After waiting for months, you are finally assigned one, and you start your sessions.

You build up a relationship and trust your psychologist – she reassures you that your discussions are confidential and that she is there to support you. Feelings, concerns and worries are shared, even thoughts that you’d never shared with anyone else. You feel safe to do so. After all, you’re talking to a professional whose job is to help people deal with feelings like yours. Then one day when you’re scrolling through social media, the algorithm presents you with a meme about psychology. You look at it, thinking you might learn something useful. Imagine how you would feel if, instead, you read this: “When your patient says ‘What do you think’ but you’d zoned out…”

Rather taken aback, you read on to see other psychologists laughing and sharing their own experiences of when they had stopped listening to their clients, including: “make a desperate rehash of the last thing you remember them saying…”, or “why don’t you tell me what you think?”

Shocked by this public sharing of what seemed to be a common experience for professionals you had previously trusted and assumed were listening closely to what you were saying, you scroll through a few more memes, seeing that there is a entire page dedicated to the experience of psychologists. You find upon looking at this page that a number of the memes refer to experiences with patients, with the following comments about them:

“One of the reasons I don’t accept hot drinks when I do community visits is because I tend to propel them from my nostrils in disbelief when someone has actually done a home practice task as planned”

“When you’ve spent all week formulating your client and you still don’t know what the f**k is going on”

“Now listen here, you little shit”

“When I worked in LD [Learning Disability] services I half expected a Demogorgon to walk into the clinic room when doing initial meetings”

“He shared personal information on a meme page”

Scrolling on with increasing concern, you then see one therapist proclaim that there “are lots of memes to be had with clients (how they treat us for example)”. The owner of the social media page agrees that he or she thinks that “making memes about clients is fine” because they are “just as fallible as we are”.

You then find to your horror that the Instagram page you’re viewing had actually previously been shut down due to ‘identifiable’ information having been shared. Yet it has clearly been re-opened. You panic, with your mind desperately trying to remember any piece of embarrassing, personal or sensitive information that you had shared with your therapist, wondering if you were the person identified. Even worse, had these professionals (including your own therapist whom you had trusted) been using you as an example, and laughing at what you had shared with them?

All of a sudden, the therapist who you thought was a professional whom you had built a trusting relationship with is now an individual who thinks it’s appropriate to publicly talk about and ridicule patients on a public site on the world wide web. Not only this, judging by the responses of her colleagues, this seems to be a standard, acceptable and enjoyable group activity.

“Crying is not an emergency”

Upon further investigation, you see that therapists’ lack of discretion extends beyond clients to their thoughts about other health professionals. Few are safe from criticism, with fellow psychologists, psychiatrists, doctors and medical-care staff all being targeted:

Looking at these jokes, you feel you’ve misjudged your therapist: you trusted her, you thought she was genuinely engaging with your story and that she wanted to help you. Instead, she and her colleagues are publicly laughing at patients like you; they have previously exposed identifiable information about patients, and they are ‘bitching’ about other health professionals in a public forum.

You wonder if your judgement of others is so poor. Clearly the trust you had was misplaced, as was your understanding of your relationship. Imagine the consequences for your mental health: the very person you put your trust in, and who was meant to help you, has damaged your wellbeing even further.

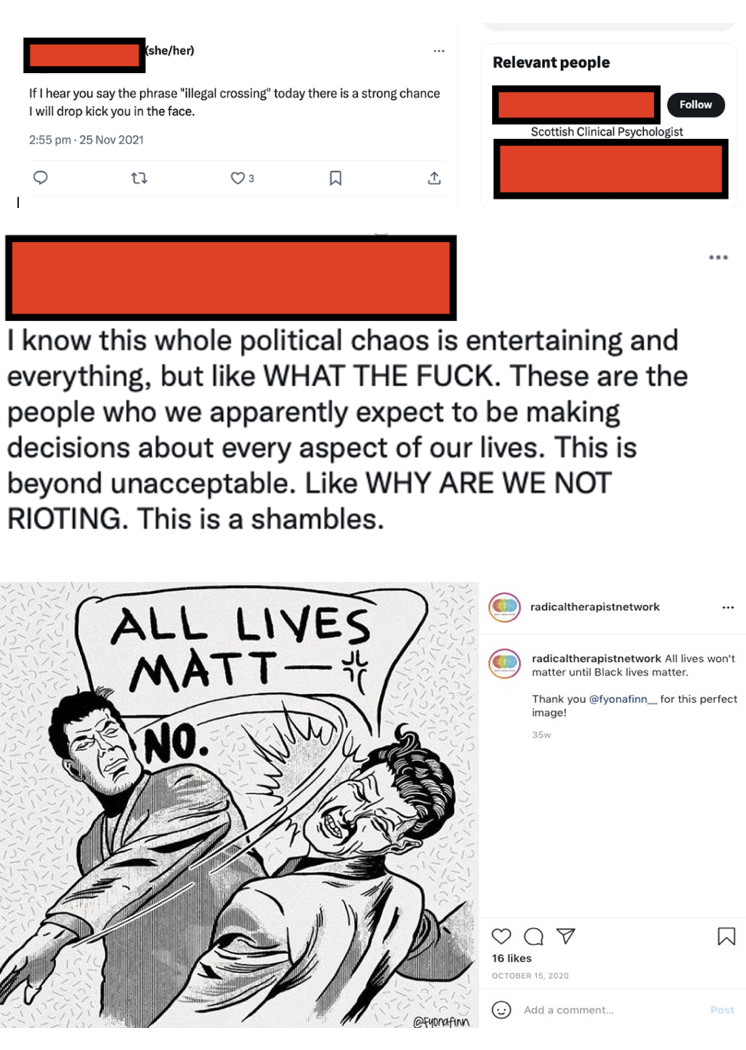

“There is a strong chance I will drop kick you in the face”

In another scenario, imagine that you’d struggled for a long time with your mental health. You don’t want medication and you know the alternative is therapy. This is a big step, and you are trying to psych yourself up to request it. However, when scrolling social media, you are hit by a number of posts that make you think twice.

Some of these posts seem to be particularly judgemental – even endorsing violence against those who hold different opinions to the therapist posting them. You read them with horror, shocked by the public displays of judgement presented by individuals who you thought were meant to be open minded, understanding and empathetic.

Many of the posts strongly condemn individuals for holding certain beliefs, and you feel concerned. You hold some of these opinions that are being condemned – clearly therapy is not for me, you think. Even when you don’t share the beliefs that are being condemned, you wonder whether that means that you can’t say certain things in therapy? Maybe you should research what you can and can’t say before you start your sessions. Your worries then escalate: could your therapist ‘cancel’ or report you for having beliefs that she doesn’t agree with? Will you upset her, will she be angry with you?

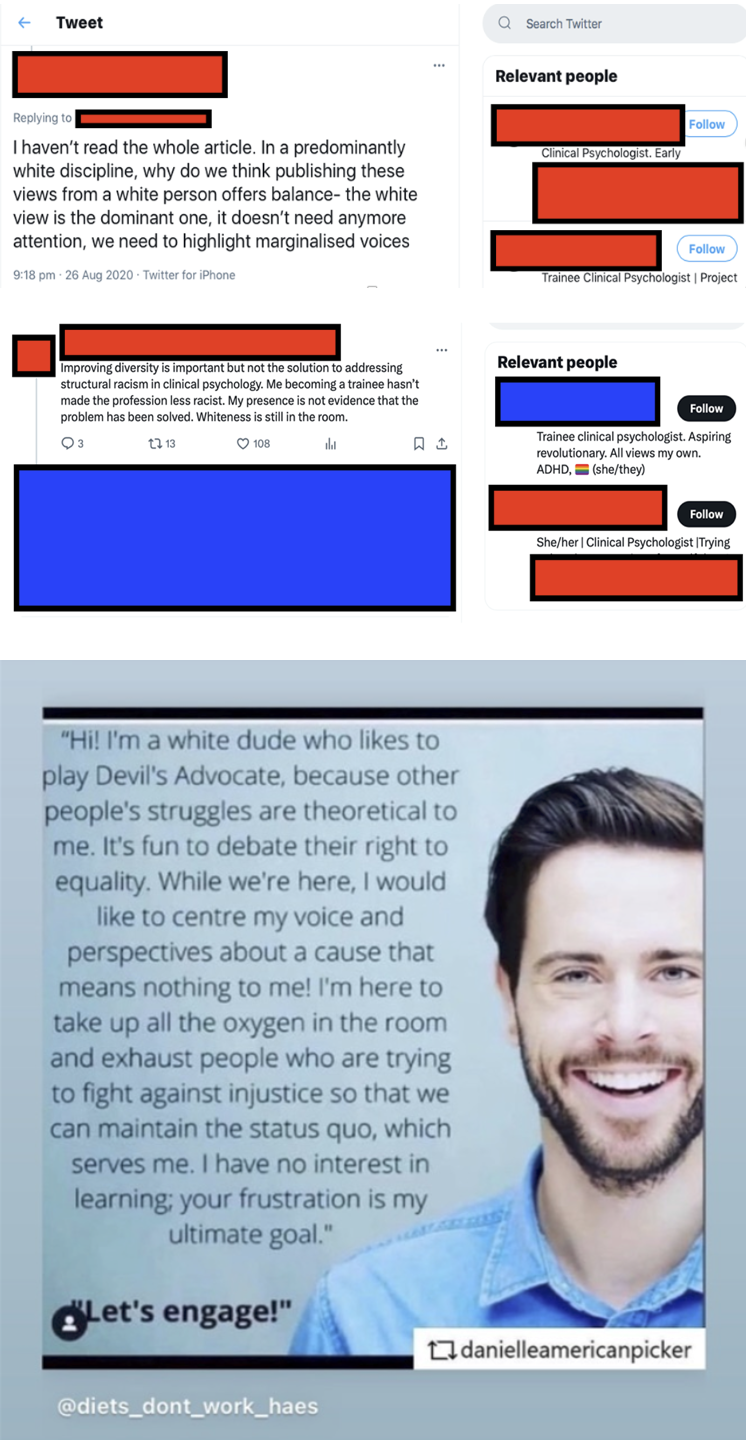

“Whiteness is still in the room”

Reading on, you are even more concerned to see that it is not only opinions that are condemned – it seems that individuals will even be judged on their immutable characteristics such as skin colour or sex. One psychologist complains about the fact that “whiteness” is “still in the room”, while another posts a disparaging meme about men. As a white male, you feel that you have already been judged: in the eyes of these therapists, you seem to be a problem that they don’t want to see or listen to – or at the very least, they hold you in distain.

“I’d be lying if I said my mental health was fully stable off my meds”

Having read these posts, you start to wonder why such individuals have decided to pursue careers as psychologists – especially when they seem to have such pre-determined (negative) ideas about groups of people. If these people only care about those they agree with – or those who are ‘like them’ – what can they bring to the table when they are working for the NHS and will be required to work with patients of a different sex, skin colour or religion? Looking further, you see that many of these psychologists seem to be in need of help themselves, voicing upset and distress at the kind of things you were expecting them to be able to advise their clients on.

For example, you see one trainee psychologist posting a stream of consciousness about her own psychological issues, another says she is “too triggered” to look at a magazine cover, another states that simply being a woman is “exhausting and scary”, while yet another states that she is unable to cope either on or off her own psychological medication.

When you see a senior consultant stating that the increasing presence of “lived experience” (i.e., psychologists who have “lived experience” of mental illness) is “the biggest game changer” she’s seen in “25 years”, you can’t help but think that if the aforementioned tweets are the consequence of the game being changed, then the field would have been much better staying as it was.

While you know that there is nothing wrong in struggling with mental health – after all, you are in the same boat – you feel uncomfortable with such a public expression of inability to cope from mental health professionals themselves. You sought advice about how you could feel better but it seems that they don’t know how to make themselves feel better either.

In the same way that you wouldn’t take your broken car to a mechanic who couldn’t fix his own car, you wouldn’t want someone who couldn’t fix their own mind to advise you on fixing yours. Of course, most people have experienced difficulty at some points in their lives, and this can develop their understanding and empathy. However, you would hope that these issues have been addressed before an individual offers advice to others – otherwise issues of risk and competence start to arise.

Summary

It is possible to argue that these are just a few ‘bad eggs’ who are very vocal on social media – and as a result they make it seem as if such behaviours are widespread. This may be true, but I invite you to search the social media accounts of clinical psychologists in your local area (especially those most recently qualified) and you will see that many, even if they don’t behave in such an extreme way, still hold similar views. This is evident when you see the responses from their peers to the aforementioned posts – they are endorsed and supported by others – these are not marginal behaviours and opinions.

As an outsider, you may wonder what on earth has brought about such an extreme departure from the professional behaviour traditionally expected of those in the mental health professions. A great deal of this is likely to be due to the wholehearted adoption of Critical Social Justice (CSJ) ideology. This is because CSJ presents the world in terms of victims and aggressors, or ‘oppressed’ and ‘oppressors’. As a result, proponents of this ideology tend to view the world in a binary way: on the one hand seeing ‘poor oppressed victims’ who need to be protected, defended and affirmed, and on the other, ‘nasty powerful oppressors’, who need to be stopped from bullying, mistreating and taking from the powerless.

According to CSJ ideology, the oppressors are bad people who need to be prevented from harming the oppressed. From this perspective, we can see how the proponents of CSJ can justify their hatred and vitriol, while still strongly believing that they are good – even nice – people, as well as competent professionals. Indeed, the more strongly and loudly they denounce, silence and even attempt to destroy those they consider the oppressors, the more virtuous they believe they are.

Another consequence of this mindset is that professional and ethical psychologists are silenced and intimidated. We hear from male trainees (males being outnumbered in the profession by women 80:20) who are silenced and disparaged in their training courses by lecturers and fellow students alike. We also know that training courses for psychologists recruit for and promote CSJ ideology, and this is one of the reasons that the field is becoming increasingly unable to offer appropriate support to patients. People with their own mental health problems, with vindictive, fragile personalities, and those with a desire to force their own opinions and beliefs on others are drawn to the field due to the opportunities it provides to develop these behaviours. If those in positions of authority in the discipline of psychology do not challenge these behaviours and traits, they are then reinforced, providing power and status to such individuals, while simultaneously reinforcing their narrative and shutting down alternative perspectives or challenges.

Ultimately, those responsible for policy-making and guidelines must be held to account – both the organisations themselves and those enabling these ideological views to spread. These organisations include the British Psychological Society, the Health Care and Professions Council and the NHS. They are of the same mindset, promoting and embedding these ideas and behaviours into policies, while steadfastly refusing to listen to any concern or criticism.

The division of the British Psychological Society in charge of clinical psychologists has become increasingly militant in its politicisation, promoting ideology over evidence and encouraging those with a similar mindset to join the profession at the expense of those with a strong scientific and research-based mindset. Indeed, the latter are dismissed as ‘White’ ‘Eurocentric’ and ‘Western’, and their expertise discarded alongside their immutable characteristics – a sign of the priorities of the discipline.

Throughout this piece, I have asked you to imagine that you are in the position of the patient, and with a quarter of the population experiencing mental health problems each year, there is a strong likelihood that either you or a loved one might be in this position at some point in your lives.

For a final time, I ask you to put yourself in the position of that patient: unless action is taken to combat the ideology that has taken over our mental health institutions, the ‘professionals’ described above are the ones who will be ‘treating’ you. You will see individuals who judge you by your skin colour, your sex, your opinions. You will see individuals who can’t look after their own wellbeing. You will see individuals who don’t have the requisite desire, ability or understanding to support you with evidence-based treatments.

Ultimately, you won’t see knowledgeable, capable professionals – you will see people who are more in need of support than you are.

And that should scare you.